Juventus 3-0 Chelsea: Di Matteo uses Hazard upfront, but Chelsea lose the game elsewhere

Spoiler

Juventus played excellently and comfortably defeated Chelsea.

Antonio Conte went with on-form Fabio Quagliarella upfront alongside Mirko Vucinic, and used Stephane Lichtsteiner rather than Mauricio Isla on the right.

Roberto Di Matteo dropped Fernando Torres in favour of Eden Hazard as a false nine – because he didn’t want to give Juventus’ three centre-backs a ‘reference point’. This meant he needed another wide player, and he wanted someone defensive-minded – this would have been Ramires were he not needed in the middle, so Cesar Azpilicueta became a cautious right-winger.

But Juventus were the superior side – their opening two goals were both aided with deflections, but they created significantly more goalscoring opportunities over the course of the 90 minutes, and put Chelsea under constant pressure.

Hazard upfront

The surprises in Chelsea’s line-up, combined with the resounding defeat, will see Di Matteo’s starting selection questioned. In fact, the moves made sense on paper and were hardly disastrous on the pitch.

The decision to start Hazard rather than Fernando Torres was completely reasonable. Torres had been extremely quiet in the first leg, not showing the appetite for physical battles against Juve’s centre-backs, nor the ability to make clever movements in the channels to get away on the break. It’s a thankless task, playing upfront alone against a back three, but Torres’ showing in the reverse fixture, combined with his poor run of form (which, realistically, now stretches back for three years), hardly made a convincing case for his selection.

It’s got the point where Hazard is more adept at playing the Torres role (that is, the role of Torres at his peak, peeling off into wider zones before sprinting in behind) than Torres. Chelsea were playing on the counter-attack in the first half, and Hazard played the false nine perfectly well. He might have missed a fine goalscoring opportunity after Oscar’s excellent run, but he created a similarly good chance with some brilliant movement and good awareness of Juan Mata’s run, and produced a fine pass to find him.

Chelsea were two composed finishes away from Di Matteo’s decision being judged a success. How would Torres have fared? It’s impossible to say – but there’s nothing to suggest he would have been a more promising outlet on the break, or a more reliable finisher in front of goal.

Of course, when Chelsea fell behind, Juventus sat back and Hazard was forced to play more of a classic centre-forward role – this was predictably unsuccessful.

Azpilicueta

Di Matteo’s second key decision was using Azpilicueta on the right of midfield, and again, this broadly worked well on. There was a huge difference in the positioning of Azpilicueta and his equivalent on the opposite side, Mata. That’s entirely natural – Azpilicueta is a full-back, Mata is a playmaker.

But while Azpilicueta kept the right flank secure in combination with Branslav Ivanovic, Chelsea’s clearest weakness in the first half was Lichtsteiner’s untracked runs from the right-wing-back position. It was he that hit the post in the opening minutes after a run behind Ashley Cole, and then later Cole was forced to clear off the line when Lichtsteiner tried to bundle the ball over the line. On other occasions, the wing-back found himself in space but wasn’t found quickly enough by the Juventus midfielders. The disparity on either side was stark – Azpilicueta forced Kwadwo Asamoah to retreat or play a sideways pass, where Lichtsteiner was free to attack.

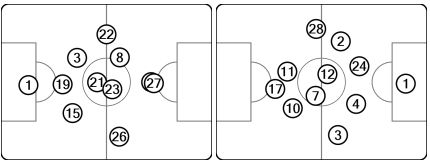

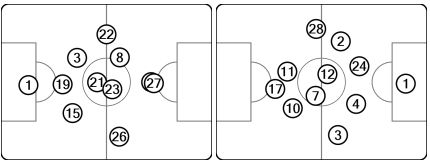

The first half average positions (courtesy of UEFA.com) - see how Mata (10) is in no

protection to protect Cole (3), while Lichtsteiner (26) is higher up than Asamoah (22)

Midfield

In the centre of the pitch, Oscar again did a decent job on Andrea Pirlo – he was unfortunate to be caught out for Juventus’ opening goal, a Pirlo shot that was turned in by Quagliarella – but Juventus’ bravery in terms of forward running was remarkable. From an early stage they got numerous players into the box, with both Claudio Marchisio and Arturo Vidal charging into goalscoring positions. Vidal found space between Ramires and Mata when Chelsea were defending, particularly when Juve attacked down the left and Ramires shuffled across the pitch.

Pirlo, too, was happy to move ahead of Oscar and risk being caught on the counter-attack – Juve were seemingly confident their surplus of centre-backs would allow them to stop breaks, although a couple of times defenders were forced into tactical fouls.

Juventus routines

In combination with the midfield running, Juve replicated their pre-arranged strategy to drag Chelsea’s defenders out of position. Both Vucinic and Quagliarella are mobile, quick but competent with their back to goal – so when one moved deep and drew a Chelsea centre-back up the pitch, the other would quickly sprint in behind. This happened a couple of times in the first half – an offside flag called a halt to one move – but it was most obvious in the second half when Quagliarella rounded Petr Cech, but couldn’t finish from a tight angle.

It was also notable that Juventus had prepared a couple of clever corner routines – one resulted in a short corner and a backwards ball into the path of Marchisio, who forced Cech into a save. Another less successful strategy was for Pirlo to chip a short corner to a player in advance of the near post, who would flick the ball into the six-yard box.

Substitutions

Di Matteo’s first substitution was predictable, replacing Azpilicueta with the more attack-minded Victor Moses – but within 90 seconds, Chelsea had conceded a goal assisted by Asamoah, who had previously been shackled by Azpilicueta.

It’s unlikely Azpilicueta would have been directly tracking Asamoah’s run – but he would have been in a deeper position than Moses was, which in turn might have pushed Ivanovic deeper and in a position to tackle Asamoah. Again, Juve’s commitment to brave runs paid off – nine seconds after a throw on the halfway line, they had four men inside the penalty box against Chelsea’s four defenders. That wrapped up the game.

Di Matteo then put on Torres for Mikel, moving Oscar deeper alongside Ramires.

Juve freshened things up with Martin Caceres replacing Lichtsteiner and Sebastian Giovinco on for Vucinic. This helped secure the win – Caceres brought both more defensive steel and renewed energy, while Giovinco kept making dangerous runs in behind a Chelsea defence playing an increasingly attack-minded game. Caceres set up Vucinic for a good chance, then made the interception that led to Giovinco scoring the third.

Conclusion

The decision to use Hazard didn’t cost Chelsea, nor did the decision to use Azpilicueta. Instead, they were prone to Juve’s midfield runs, the movement of their strikers, and the runs of Lichsteiner from right-wing-back (Asamoah on the other side only became a significant problem after Azpilicueta departed).

In fact, they were were most exposed in the least experimental and least controversial parts of Di Matteo’s starting XI. That will prompt questions about his overall strategy at Chelsea, but his specific tactics for this game weren’t disastrous.

Antonio Conte went with on-form Fabio Quagliarella upfront alongside Mirko Vucinic, and used Stephane Lichtsteiner rather than Mauricio Isla on the right.

Roberto Di Matteo dropped Fernando Torres in favour of Eden Hazard as a false nine – because he didn’t want to give Juventus’ three centre-backs a ‘reference point’. This meant he needed another wide player, and he wanted someone defensive-minded – this would have been Ramires were he not needed in the middle, so Cesar Azpilicueta became a cautious right-winger.

But Juventus were the superior side – their opening two goals were both aided with deflections, but they created significantly more goalscoring opportunities over the course of the 90 minutes, and put Chelsea under constant pressure.

Hazard upfront

The surprises in Chelsea’s line-up, combined with the resounding defeat, will see Di Matteo’s starting selection questioned. In fact, the moves made sense on paper and were hardly disastrous on the pitch.

The decision to start Hazard rather than Fernando Torres was completely reasonable. Torres had been extremely quiet in the first leg, not showing the appetite for physical battles against Juve’s centre-backs, nor the ability to make clever movements in the channels to get away on the break. It’s a thankless task, playing upfront alone against a back three, but Torres’ showing in the reverse fixture, combined with his poor run of form (which, realistically, now stretches back for three years), hardly made a convincing case for his selection.

It’s got the point where Hazard is more adept at playing the Torres role (that is, the role of Torres at his peak, peeling off into wider zones before sprinting in behind) than Torres. Chelsea were playing on the counter-attack in the first half, and Hazard played the false nine perfectly well. He might have missed a fine goalscoring opportunity after Oscar’s excellent run, but he created a similarly good chance with some brilliant movement and good awareness of Juan Mata’s run, and produced a fine pass to find him.

Chelsea were two composed finishes away from Di Matteo’s decision being judged a success. How would Torres have fared? It’s impossible to say – but there’s nothing to suggest he would have been a more promising outlet on the break, or a more reliable finisher in front of goal.

Of course, when Chelsea fell behind, Juventus sat back and Hazard was forced to play more of a classic centre-forward role – this was predictably unsuccessful.

Azpilicueta

Di Matteo’s second key decision was using Azpilicueta on the right of midfield, and again, this broadly worked well on. There was a huge difference in the positioning of Azpilicueta and his equivalent on the opposite side, Mata. That’s entirely natural – Azpilicueta is a full-back, Mata is a playmaker.

But while Azpilicueta kept the right flank secure in combination with Branslav Ivanovic, Chelsea’s clearest weakness in the first half was Lichtsteiner’s untracked runs from the right-wing-back position. It was he that hit the post in the opening minutes after a run behind Ashley Cole, and then later Cole was forced to clear off the line when Lichtsteiner tried to bundle the ball over the line. On other occasions, the wing-back found himself in space but wasn’t found quickly enough by the Juventus midfielders. The disparity on either side was stark – Azpilicueta forced Kwadwo Asamoah to retreat or play a sideways pass, where Lichtsteiner was free to attack.

The first half average positions (courtesy of UEFA.com) - see how Mata (10) is in no

protection to protect Cole (3), while Lichtsteiner (26) is higher up than Asamoah (22)

Midfield

In the centre of the pitch, Oscar again did a decent job on Andrea Pirlo – he was unfortunate to be caught out for Juventus’ opening goal, a Pirlo shot that was turned in by Quagliarella – but Juventus’ bravery in terms of forward running was remarkable. From an early stage they got numerous players into the box, with both Claudio Marchisio and Arturo Vidal charging into goalscoring positions. Vidal found space between Ramires and Mata when Chelsea were defending, particularly when Juve attacked down the left and Ramires shuffled across the pitch.

Pirlo, too, was happy to move ahead of Oscar and risk being caught on the counter-attack – Juve were seemingly confident their surplus of centre-backs would allow them to stop breaks, although a couple of times defenders were forced into tactical fouls.

Juventus routines

In combination with the midfield running, Juve replicated their pre-arranged strategy to drag Chelsea’s defenders out of position. Both Vucinic and Quagliarella are mobile, quick but competent with their back to goal – so when one moved deep and drew a Chelsea centre-back up the pitch, the other would quickly sprint in behind. This happened a couple of times in the first half – an offside flag called a halt to one move – but it was most obvious in the second half when Quagliarella rounded Petr Cech, but couldn’t finish from a tight angle.

It was also notable that Juventus had prepared a couple of clever corner routines – one resulted in a short corner and a backwards ball into the path of Marchisio, who forced Cech into a save. Another less successful strategy was for Pirlo to chip a short corner to a player in advance of the near post, who would flick the ball into the six-yard box.

Substitutions

Di Matteo’s first substitution was predictable, replacing Azpilicueta with the more attack-minded Victor Moses – but within 90 seconds, Chelsea had conceded a goal assisted by Asamoah, who had previously been shackled by Azpilicueta.

It’s unlikely Azpilicueta would have been directly tracking Asamoah’s run – but he would have been in a deeper position than Moses was, which in turn might have pushed Ivanovic deeper and in a position to tackle Asamoah. Again, Juve’s commitment to brave runs paid off – nine seconds after a throw on the halfway line, they had four men inside the penalty box against Chelsea’s four defenders. That wrapped up the game.

Di Matteo then put on Torres for Mikel, moving Oscar deeper alongside Ramires.

Juve freshened things up with Martin Caceres replacing Lichtsteiner and Sebastian Giovinco on for Vucinic. This helped secure the win – Caceres brought both more defensive steel and renewed energy, while Giovinco kept making dangerous runs in behind a Chelsea defence playing an increasingly attack-minded game. Caceres set up Vucinic for a good chance, then made the interception that led to Giovinco scoring the third.

Conclusion

The decision to use Hazard didn’t cost Chelsea, nor did the decision to use Azpilicueta. Instead, they were prone to Juve’s midfield runs, the movement of their strikers, and the runs of Lichsteiner from right-wing-back (Asamoah on the other side only became a significant problem after Azpilicueta departed).

In fact, they were were most exposed in the least experimental and least controversial parts of Di Matteo’s starting XI. That will prompt questions about his overall strategy at Chelsea, but his specific tactics for this game weren’t disastrous.

Comment